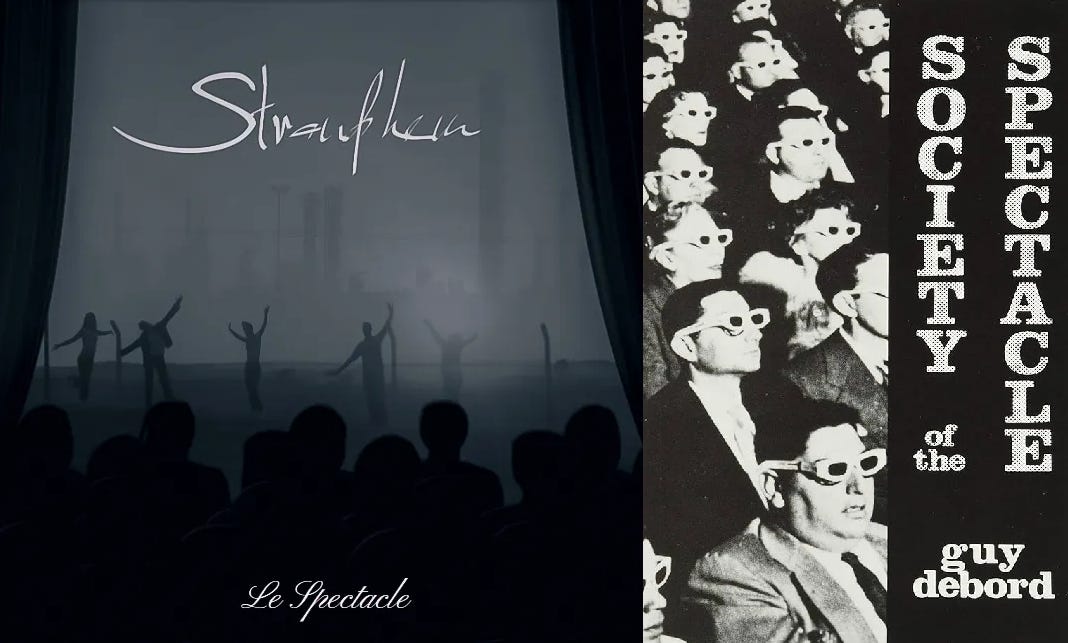

'Le Spectacle' : A Musical Ode to Guy Debord

Deep dive into the the book that inspired the album.

I first got my hands on Guy Debord’s 1967 work of social critique The Society of the Spectacle when I was visiting Bordeaux in the summer of 2022. I was strolling through a big book store somewhere in the center of the city, and figured I’d use it as an opportunity to collect a few classic works of French postmodern literature before heading back home the next day. When I asked the clerk where I could find Debord’s book, instead of referring me to some shelf somewhere or looking it up on his computer, he without any hesitation took me directly to the exact spot where the book was located - which already then made me realize I was indeed asking for a classic work of French critical theory and not some obscure book confined to the dustbins of history. French being my mother tongue, I picked it up in its original version along with some Foucault books and proceeded to go on my merry way.

The book is rather short, but it spoke to me in a way that few other works in the past at that point had. There was something about the way Debord painted this societal picture of sorts that felt like it managed to put into words an inaptitude I myself had had at phrasing this deep-seated sense of falsity and insincerity present in our modern day Western societies. Something I myself hadn’t been able to explain or conceptualize in any consistent manner, but Debord succinctly did: society today is at its core nothing more than a collection of commodity spectacles presented to us as objective reality.

Defining Spectacles

I remember one day being in a book store in Finland (not a properly academic book store like the one in Bordeaux but rather one of these smaller ones you find in your typical mall or airport), and I was looking at their non-fiction section. Presented almost like trophies against the wall were a series of biographies of people who society considers to be important figures: your Barack & Michelle Obama, Robert Mueller, Hillary Clinton, Jenni Haukio (wife of the Finnish president Sauli Niinistö), Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, and many other such individuals very much in the same discursive universe - i.e. the same ideological camp, same class adherence, similar types of power position, etc. These are, across the Western world at least, the figures whose lives are deemed worthy of learning about, to the point that their often self-gratifying biographies boasting their many virtues and potentially graceful failings cannot be escaped from. These are the stories our society for the most part believes need to be told.

Instead, I started reading The Society of the Spectacle, and only a few pages in, Debord drops the following line:

“The spectacle is the ruling order’s nonstop discourse about itself, its never-ending monologue of self-praise, its self-portrait at the stage of totalitarian domination of all aspects of life.”

These few words really managed to put the thoughts I had had in the bookstores within a bigger context - the context of the Debordian spectacular society.

In his book, Debord provides many different explanations as to what these spectacles are, approaching them from several different angles. At their very core, these spectacles create “a social relation between people that is mediated by images.” Here ‘images’ is not to be understood entirely literally, but rather as a series of representations or messages conveyed in varying media formats - i.e. non-human elements conveying often self-serving and self-referential information. Combining that with the notion of the never-ending monologue of the dominant class, spectacles are all these often ignored aspects of society whose repeated presence and articulation frame and dictate our view of the world for us in advance.

It makes a lot of sense that Debord wrote his book at a time where the radio, television, magazines, and advertising as an industry in its own right all were exploding in prominence and social importance, and mass consumerism spearheaded by never before seen levels of abundant industrial commodity production became the main ideological framework for societal prosperity - abundant commodities that above all needed to be sold to sustain economic growth. It would be more difficult to draw a similar social critique in the eras preceding the advent of mass media where images where scarce and information limited, but Debord’s very point is that it is these mass mediums that are distorting our perception of reality, and with it our own direct relation with the material world and our relation with other human beings.

For Debord, the spectacle

“presents itself as a vast inaccessible reality that can never be questioned. Its sole message is: ‘What appears is good; what is good appears.’ The passive acceptance it demands is already effectively imposed by its monopoly of appearances, its manner of appearing without allowing any reply”.

I believe the notion of appearing without allowing any reply is very important here, namely because mass media traditionally has functioned as a one-way avenue for political discourse: the consumer of mass media is intrinsically passive, thus making lies, half-truths, propaganda, or other forms of skewed messaging difficult to rebut in a public fashion. This makes it the perfect vehicle for the creations of a wide variety of spectacles - political or commercial in nature - to impose a specific worldview on the docile masses: the world view where the commodity is King.

As Debord puts it:

“The root of the spectacle is that oldest of all social specializations, the specialization of power. The spectacle plays the specialized role of speaking in the name of all the other activities. It is hierarchical society’s ambassador to itself, delivering its official messages at a court where no one else is allowed to speak. The most modern aspect of the spectacle is thus also the most archaic.”

Debord was very concerned with how these spectacles were shifting our very relationship to the world. For him, the world had now moved first from a life of being to one of having, and finally from one of having into one of appearing. The reasons for this is mostly economic, as we know that the sign value of commodities has in consumerist societies in many ways overtaken the order of actual use value. In Baudrillardian terms (the so-called French ‘high priest of postmodernity’), sign value is that value which commodities can have that elevate them based on how our association with them seems to advance our own value as individuals. This is a big component of a life based around appearing, as for example brands - which are most often nothing but loaded signs - will dictate our relationship to a commodity based on its accepted social value. Suddenly, our relationship to ourselves and others becomes mediated by this forth-bringing of commodity sign value: “all ‘having’ must now derive its immediate prestige and its ultimate purpose from appearances”, Debord succinctly writes.

Where this becomes truly fascinating for us in the 21st century is of course in the age of social media and its pinnacle of mediocrity: influencer culture. There seems to be nothing more void of essence than an entire fictive, online culture of vanity centered around the sign value of objects. While the influencers often will reduce themselves to the status of commodities (“branding yourself”), they will often do so by showcasing their value in relation to Master Signifiers (i.e. key discursive elements around which meaning is formed; also known as the Lacanian point de capiton, or Laclauian nodal point) of capitalist consumerist society. For example, making sure that their content (‘content’ being nothing more than mass-produced art in service of profitability and marketability) relates to material things our society of spectacles values, such as fancy cars, designer brands, luxurious hotels, the newest tech, dreamy foreign resorts, fit bodies, etc.

Instagram has as of 2024 almost 700 million users, about 75% of which have more than a thousand followers, and 25% have 10.000 and above. This means we’re talking about millions of users who now fall under a certain category of ‘famous nobodies’. People whose fame is purely virtual, appearing only as a number on a webpage that somehow signals the social value of the individual. And it is fascinating still that, should we think back to Debord’s criticism of the one-directional mass media landscape, that social media supposedly breaks that relationship and renders it bidirectional. Yet still, what we experience across the board is a widespread desire for individuals to elevate themselves above the rest by completely internalizing the social imaginary of capitalist consumerist culture, transforming themselves into yet another spectral dimension of the spectacle - yet another shining beam of our prevailing ideology.

The ultimate goal essentially is to resonate meaning, to ‘influence’, to become part of the monologue. Of course that would be the case in a culture where the sign value of objects ranks highest, so what could be better than commodifying yourself while boasting your own sign value, your own personal brand? This way influencers can plead to advertisers to use them as a marketing commodity that supposedly heightens the value of the product they want to sell, hoping that some of their perceived social value as signs will brush off onto the commodity they hope to sell. Becoming the ultimate commodity - the ultimate embodiment of appearances - is thus how you “make it” in the spectacle (congratulations on becoming ‘nothing’ in its most elemental definition!)

It is to be noted that trying to advance social consciousness towards political and material aims is rarely the approach taken by influencers - and if they do, it is merely to advance certain vague and still individualist milquetoast philosophies of “positivity”, “happiness”, good health or tolerance. The reason is of course obvious, as a good commodity needs to be frictionless and void of any kind of radicalism in order to appeal to the largest possible audience. Don’t rock the boat too much or you might loose your spectacular dimension.

Breaking Free from the Spectacle

Debord had varying ways of attempting to break free from our society of spectacles. He started the ‘Situationist International’ movement which focused on a return towards being rather than appearing, and engaged in détournement - an art form that seeks to take elements from the spectacle (such as an ad), and ‘overturning’ it, meaning altering it in such a way as to bring forward its nature as a spectacular element.

I will not personally claim to have a silver bullet against the spectacle and our commodity culture. This is at its core a systemic issue, and my belief is that systemic issues require systemic solutions. Nonetheless, I think it’s important to take some distance to whatever it is we’re being ‘sold’ - not purely from a material point of view, but also ideologically speaking. Just because some particular commodity, idea, belief system, individual, or ideology gets presented to us as sublime and worthy of our desires, that doesn’t mean that we should accept it as such.

To quote Jean Baudrillard: “We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning“, hence essentially what needs to be reaffirmed is meaning itself within our vast ocean of meaninglessness. Meaning comes forth in many ways, but in today’s world it very much needs to be parsed through. If the mantra of the social spectacle is indeed that of ‘what appears is good; what is good appears’, then this very notion is the one that needs to be rejected. Most of the time, what is presented to us is in fact not good, and the good things in life only appear if they are commodifiable or politically useful to our neoliberal status quo (which means very, very seldom).

The society which the spectacle serves to justify, legitimize, and preserve, is one whose core principles are currently leading to the ruin of our natural environment as well as our mental and physical well-being; and sadly, it is easy to maintain such a power structure over a population which is struggling to create deeper meaning in the world, as we become continuously atomized and individualized through our para-social relationship with objects and fractured relationship with others.

When politics is no longer presented to us as a struggle with an aim, but rather as an array of problems requiring individual solutions, we essentially void politics of meaning. In today’s world, personal responsibility has completely overtaken social responsibility as the driver of progress, and this is not surprising when the spectacle continuously reinforces these values - commodification always singles out that which it advances, and every commodity in its fetishistic way (in the Marxian sense) stands alone in radiating its value, only backed by the symbolic and mystifying might of the spectacle. Pointing out the perverted value of the commodity within the spectacle, Debord writes:

“The world at once present and absent that the spectacle holds up to view is the world of the commodity dominating all living experience. The world of the commodity is thus shown for what it is, because its development is identical to people’s estrangement from each other and from everything they produce.”

It is because of this domination of the commodity at the core of our living experience that we as humans or as citizens more and more become referred to as consumers first and foremost. Our main role in society has become directly associated with our ability to purchase and our ability to engage within the world of commodities. This is of course a rather obvious culmination of capitalism, as consumerism is the very social function which sustains it entirely. If we would stop buying things, capitalism would essentially collapse on its own (which is why the best ‘advice’ we are given during each recession that tend to bankrupt the masses is to ‘buy more stuff’ to keep the economy afloat, despite most not being able to afford it).

So I think this is what I will leave you with before all of this turns into a book of its own. There is a lot more to The Society of the Spectacle which I haven’t even gotten into in this piece so I can therefor warmly recommend grabbing a copy and experiencing it for yourself. It’s not a particularly long read and not the thickest work of theory I’ve read although it does have a bit of a unique writing style (especially in its format). I particularly recommend the version published by Unredacted Words as it was published particularly with the purpose of making Debord easier to understand (both in the way that it was translated from its original French, and with the many footnotes providing context and explanations throughout the book). Debord also released an addendum to it a few decades later called Comments on the Society of the Spectacle which revisits some of the concepts from the original book. He died shortly after because of health reasons, best encapsulated by this self-deprecating quote of his:

“Although I have read a lot, I have drunk even more. I have written much less than most people who write, but I have drunk much more than most people who drink.”

In many ways, Guy Debord let the spectacle get the best of him, as attempting to resist it can be a dauting task. Once unveiled, the spectacle can also present itself as highly overwhelming and soul-crushing in its suffocating presence.

So for the sake of your own physical and mental health, I would advise to consider the following:

Don’t get too caught up in social media. Take some healthy distance to it if needed, and make sure the people and pages you follow are at least remotely thought provoking and not reinforcing or feeding into the beast that is modern spectacular society.

Don’t go too far in your personal commodification. I understand it might be needed to some extend in our competitive capitalist culture (especially on the job market), but remember your humanity and the humanity of others.

Rethink your approach to material consumption. Commodities will not bring you long term happiness, overconsumption is bad for the environment, and it sustains the economic model which rots our world.

Reject the value system of the spectacle, as it is probably one of the worst yet most resilient one humanity has ever had to face. It kills any community it touches, and in its disavowal of meaningful antagonisms serves as a breeding ground for fascist revival.

Read theory, or die trying. That’s just a motto, but feeding your brain the good stuff is never a bad idea. It opens your horizons and makes you a more complete person, and maybe most importantly provides you with the analytical tools to better understand the world around you. And if you’re not a big reader, consider some other ways of getting into critical theory. For example some great YouTube channels I can recommend are Epoch Philosophy, Then & Now, Plastic Pills, CCK Philosophy, Theory & Philosophy, and Ryan Chapman (amongst other).

And if you haven’t, listen to Le Spectacle from the following platforms:

Youtube: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ruKMMgOrkXU

Spotify:

...

Youtube Music: https://music.youtube.com/channel/UCwunOsmZy4__gjNm-37DBRA

Tidal: https://listen.tidal.com/album/287552127/track/287552128

Deezer: https://www.deezer.com/da/album/426284657

Apple Music: https://music.apple.com/us/artist/strandhem/1680937489

Bandcamp:

Until next time.